They lined the pit with well-cut planks,

and when the body was laid in,

they roofed it close with more wood.

Then they heaped earth down,

to preserve the corpse, worthy vessel

of its soul, from rain and time’s ruin.

Yesterday we found it.

They lined the pit with well-cut planks,

and when the body was laid in,

they roofed it close with more wood.

Then they heaped earth down,

to preserve the corpse, worthy vessel

of its soul, from rain and time’s ruin.

Yesterday we found it.

You know the cure b ut you can’t take it.

ut you can’t take it.

Something blocks you – something, nothing:

the slightest, slenderest wall of glass

keeps you from stepping out of hell

and into the full monty, double-whammy,

ding-dong-daddy of life in the world.

A veil as thin as gossamer … but not even

the atom bomb your grandfather built

could blow a way through. Strange,

this, so strange: sitting in a meeting

with your soul on fire, and no one

can even see the smoke.

Still standing on that hill,

watching our corrupted dreams

drive away.

David Kenan (1930-1997). Novelist and essayist. His books include The Intercessor, Stroke of Twelve, Meditational Deities and No Longer Expecting an Answer.

Excerpt from Stroke of Twelve: “The place had a river view, the kind you pay big money for. The night had taken on yet another nature. Gray mist rising and moving off the water. There was no particular shape to the shore, just a high black wall. I cracked open a window to the damp. Sounds poured in, tangled in the mist. No highway sounds (you pay good money for that too), but distant tugs, low motor-rumble slicing the water, and wind in wet trees.

“I came here busted a year ago: a petrified heart, a closed oyster-can. Then she came along and suddenly I could feel a melodic note rising, a note that seemed to reveal the ultimate clarity of some thought — the real thing, the first utterance of a truth, not a worn-out ragged echo dying in the air. A dangerous thing, a dangerous thing to be in such a state. At the mercy of someone else’s secret heart. At the mercy of your own. But this has got to be learned; there isn’t any getting around it.”

Miriam Zacharias. Professor of Astrophysics, Cambridge University. Also author of three volumes of poetry: A Strange Almost, Forever Unremembered, Go to Hell and Kiss Me.

“Saturn setting in the midnight sky.

Milky Way shifting south with the breeze.

Perseids thinning as the storm moves on.

Cyprian. Cyprian. Cyprian.”

Genevieve Daston (1928-2015), Professor of English Literature, Illion College; Blake scholar. Author of The Lost Traveller’s Dream, A Dark Hermaphrodite, and The Moment Satan Cannot Find, among others. “At night before I go to bed, I open the Collected Works at random and read a passage — a superstition, a ritual, far removed from any scholarly practice. So very often, the passage infects my dreams — if not that very night, then soon thereafter. Last night I came upon these lines: ‘Mutual Forgiveness of each Vice,/Such are the Gates of Paradise.’ I wonder what that will conjure up!”

Louis Bernofsky (1929-2002). Poet. Books include Balzarines, Last Screw, The Usual Plan and his award-winning collection, The First Dead American Whale. “I took a wrong turn. I was a lousy poet. I should’ve been a pipefitter, like my old man. That’s what the world needs more of: pipefitters who love poetry, not another lousy poet.”

Napoleon’s Horse

Napoleon’s horse belongs to Elizabeth Taylor now.

The grand steed he rode into Moscow now feeds contentedly

in a Welsh barn. Sometimes a groom takes him out

for a ride, to get the blood going, and to feel, for a moment,

like Napoleon. (Who was still, at this time, a strong folk memory.)

On the rarest of occasions, Elizabeth Taylor comes by.

She feeds the horse carrots, and asks knowledgeable questions,

but she never rides him. She thinks: it’s a miracle he’s still alive.

She thinks: What if I damaged him? What if a century and a half

just crumbled away into dust beneath me? She feeds him,

she talks to the grooms and she goes away.

Sometimes she feels saddened by the encounter;

sometimes she feels a lightness she could never explain.

Where is the ghost in this great misfiring,

the malevolent spirit fouling the lines,

tying hard knots here, loosing poison there,

everywhere constricting and silting up the flow?

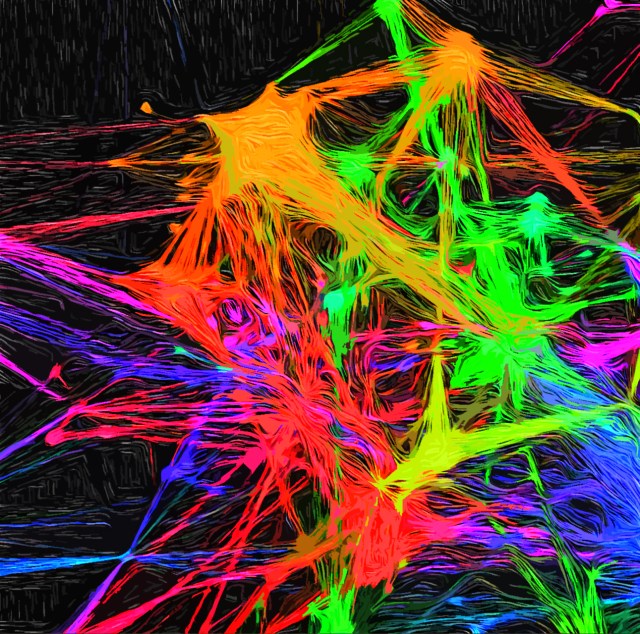

The apparition was glimpsed on the far side of the creek. It shimmered in a cloud of strange light, yet cast no reflection on the water. My camera, already set up to capture the quiet morning scene, instead impressed this wondrous spectacle upon its plates. Sometimes it appeared to be a single figure, at other times there looked to be a second by its side. Some human aspect it seemed to have, but with an otherworldliness so strong and frenzied it left one almost deranged. Yet I held steady, the camera on its stand held steady – and so too the apparition, at least long enough for the image to form. Then, as suddenly and soundlessly as it came, it dissolved into the morning air, and the world, which had seemed frozen or spellbound, set at some far remove, was suddenly released back into its normal flow.