“‘The Additional Thing’ (below) was the final poem written by American poet John Turner Wiley before his death at age 66 in a 2007 car crash in the Blue Ridge Mountains.” Pencil sketch.

The Additional Thing

It takes 14 seconds for the soul to burn.

The process begins with a synaptic firing,

igniting a network of celestial complexity,

meshing, near instantaneously, with hormonal flows

and multiple streams of sensory data

from the interface of the nervous system

with the world beyond.

The world within, comprised of these operations,

and the additional thing that creates

continuity of self, resonance of memory,

and the conscious and unconscious weaving of context

from which meaning and reality are composed,

is in 14 seconds overcome by the fire

and dissolves in a heap of unconsecrated ash.

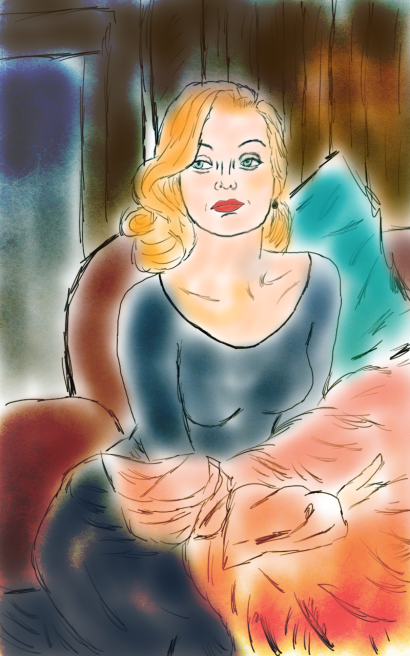

When she was younger, she loved him for his body, and for her body. In a cloud of hormones lit by bolts of giddy neurons, in the freshness and chaos and newness of everything, everywhere, inside and out, she saw him glowing, gilded, in gauzed light. She saw depths of soul and boundless strengths, in him and in herself. When she took him inside herself, she knew a kind of melting and merging with the universe; in this most earthy act, she felt otherworldly. And if he made some unworthy remark afterward – something crass, prosaic, juvenile – she would hear but not register it, letting her comprehension glance away, to keep the myth intact. He didn’t always do this, of course; sometimes as she lay with her head on his chest, he’d struggle to find words to express the higher feelings coursing through him, something far beyond his eloquence, perhaps beyond the reach of any language. That these too were banalities, stitched together from threadbare clichés, didn’t matter to her. She translated his words into the unutterable flow of feeling around them in the moment, their spent bodies pressed together, his hand brushing back her hair.

When she was younger, she loved him for his body, and for her body. In a cloud of hormones lit by bolts of giddy neurons, in the freshness and chaos and newness of everything, everywhere, inside and out, she saw him glowing, gilded, in gauzed light. She saw depths of soul and boundless strengths, in him and in herself. When she took him inside herself, she knew a kind of melting and merging with the universe; in this most earthy act, she felt otherworldly. And if he made some unworthy remark afterward – something crass, prosaic, juvenile – she would hear but not register it, letting her comprehension glance away, to keep the myth intact. He didn’t always do this, of course; sometimes as she lay with her head on his chest, he’d struggle to find words to express the higher feelings coursing through him, something far beyond his eloquence, perhaps beyond the reach of any language. That these too were banalities, stitched together from threadbare clichés, didn’t matter to her. She translated his words into the unutterable flow of feeling around them in the moment, their spent bodies pressed together, his hand brushing back her hair. on’t get the shiver as often as I used to. The semi, quasi (pseudo?) epileptic spasm that re-sets my psyche, restores it to its more natural state, after a particularly acute attack of the strange mental ailment that has accompanied me for many decades, for the whole of my adult life. The shiver comes so rarely now that when it happens, I’m startled by the sudden memory of how often it used to serve me, help me, restore me for a time. And even further, by the memory of how it used to come even before the onset of my mental ailment, how it was once an integral, secret, precious aspect of my essential, healthful nature. In those days, it came not as a solace or restorative, but as a piercing, heightened sense of being, as a … I honestly can’t describe it. But I do think those early instances were similar to accounts I’ve read of the intense feelings of well-being, connection and transcendence that some people with epilepsy experience just before a fit. It was never so cosmic as, say, Dostoevsky describes, and it was never followed by the pain and anguish of an actual epileptic fit. But this is the closest I can come to describing what I experienced – and, in the rarest moments, still experience. Nowadays, given the high and persistent level of mental anguish caused by the affliction, the energy of the shiver, when it comes, is taken up almost entirely with simply getting me back to something resembling an even keel in the most ordinary way; there’s not enough energy left in it to elevate me to a higher plane, as in my younger days. Still, I’m grateful that it has not entirely abandoned me.” Pencil sketch.

on’t get the shiver as often as I used to. The semi, quasi (pseudo?) epileptic spasm that re-sets my psyche, restores it to its more natural state, after a particularly acute attack of the strange mental ailment that has accompanied me for many decades, for the whole of my adult life. The shiver comes so rarely now that when it happens, I’m startled by the sudden memory of how often it used to serve me, help me, restore me for a time. And even further, by the memory of how it used to come even before the onset of my mental ailment, how it was once an integral, secret, precious aspect of my essential, healthful nature. In those days, it came not as a solace or restorative, but as a piercing, heightened sense of being, as a … I honestly can’t describe it. But I do think those early instances were similar to accounts I’ve read of the intense feelings of well-being, connection and transcendence that some people with epilepsy experience just before a fit. It was never so cosmic as, say, Dostoevsky describes, and it was never followed by the pain and anguish of an actual epileptic fit. But this is the closest I can come to describing what I experienced – and, in the rarest moments, still experience. Nowadays, given the high and persistent level of mental anguish caused by the affliction, the energy of the shiver, when it comes, is taken up almost entirely with simply getting me back to something resembling an even keel in the most ordinary way; there’s not enough energy left in it to elevate me to a higher plane, as in my younger days. Still, I’m grateful that it has not entirely abandoned me.” Pencil sketch.

u say I betrayed the Party? I did worse than that: I betrayed the Revolution. I betrayed the Revolution when I embraced the bureaucratism of the General Secretary and helped build a whole new ruling class to oppress the workers and peasants. I betrayed the Revolution when I accepted the General Secretary’s anti-Marxist, anti-Leninist formulation of socialism in one country. I betrayed the Revolution when I stayed silent as the General Secretary purged the Party of those w

u say I betrayed the Party? I did worse than that: I betrayed the Revolution. I betrayed the Revolution when I embraced the bureaucratism of the General Secretary and helped build a whole new ruling class to oppress the workers and peasants. I betrayed the Revolution when I accepted the General Secretary’s anti-Marxist, anti-Leninist formulation of socialism in one country. I betrayed the Revolution when I stayed silent as the General Secretary purged the Party of those w